Search this site

Jerry Uelsmann, The Artist Who Turned Photography Upside Down

In the 1960s, if you visited the darkroom at the University of Florida (UFL), you might see students carrying wet prints to show their teacher, Jerry Uelsmann. His classes were exceedingly popular; he allowed students to call him by his first name, and he was known to smoke cigars and occasionally pop popcorn during class. That signature sense of humor and playfulness runs through Moa Petersén’s new book Eighth Day Wonder, a biography of her friend, Jerry Uelsmann, the man who turned the photography world upside down.

Petersén, an art history scholar who first met Uelsmann in 2016, spent years on the biography. It’s a book about an individual, but it’s also about a singular moment in the history of photography, as more artists challenged the conventions of “straight photography” and experimented in the darkroom.

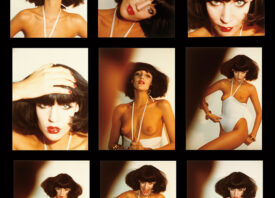

By “breaking the rules” established by those who came before him, Uelsmann helped redefine what photography could be. In stark contrast to the purist ideals of the time, his work didn’t capture an external reality but expressed an internal vision. Using multiple enlargers (as many as seven) and countless negatives, he placed images on top of one another to create impossible montages, composed of many layers.

In the age of Photoshop, it’s easy to take for granted what Jerry Uelsmann did in the darkroom, but as Petersén explains, it was nothing short of revolutionary. The idea that a photograph could be therapeutic and capture the unseen, hidden contours of the human imagination—revealing our memories, fears, and desires—was both thrilling and unsettling. Similarly, the notion that a photograph could be made after the moment when the shutter was released—e.g. in the darkroom—felt liberating.

At the time, some insisted his work was “not photography.” Uelsmann countered with the simple fact that all his images were made using materials from a photography shop: what could they be, if not photographs? It’s no wonder Uelsmann’s classes filled up quickly, as young photographers embraced that characteristic rebel spirit.

While Uelsmann’s photographs have recurring motifs—eyes, trees, hands, shells, and nuts among them—our interpretations are highly subjective, as each of us will project our own memories and emotions onto every layer. While some have dubbed him a Surrealist, he’s an artist who defies easy categorization, and Petersén accepts and celebrates the true complexity of his work and legacy.

In many ways, Uelsmann’s photographs are as mysterious and elusive as the vast natural landscape that surrounded him and informed much of his work. His darkroom sat in a wild corner of Gainesville, Florida, where alligators roamed and oak trees grew tall. In that darkroom, Jerry Uelsmann created entirely new worlds, unbound by the rules of space and time. Up became down, and past became present.

The title of Petersén’s book, Eight Day Wonder, references something Ansel Adams once said: “God created the earth in six days, and on the seventh day he looked down on the earth and thought, ‘Maybe some things need to be changed.’ So he created Jerry Uelsmann.”

Although Jerry Uelsmann never got a chance to see the final result of this biography, out now by Kehrer Verlag, he comes to life once more throughout its pages. He and Petersén remained friends until his passing in 2022. He talked with her about the place we go when we die—wherever and whatever it might be. Perhaps unsurprisingly, he called it the “big darkroom.”

Further reading:

• Surreal Photography Helps An Artist Cope During a Time of Grief

• Enchanting Photos from a Cabin in the Woods