Search this site

Photographer Diana Markosian’s Look at Chechen Women and Islam Revival

Seda Malakhadzheva, 15, sits beside her friends as they adjust her hijab. She started wearing the headcovering a year ago.

Gym class at School No 1 in the Chechen village of Serzhen-Yurt. The schoolgirls, all dressed in skirts with their heads wrapped in headscarves, say gym clothes violate Muslim dress code.

After decades of war and religious repression, Chechnya, a Russian republic located in North Caucasus, is going through Islamic revival. In her photo series Goodbye My Chechnya, Russian-born, Armenia-based photographer Diana Markosian shows what this revival means for Chechen women.

How did Goodbye My Chechnya begin?

“I was 20 when I took my first trip to the North Caucasus. Over the next year, I continued to travel to Chechnya to work on assignments, both self-initiated and commissioned. At a certain point, I realized it didn’t matter whether I had a commissioned assignment, I had to be in Chechnya and used every excuse to travel there.

“In the beginning, it was hard for me to relate to the people I photographed. The region witnessed two decades of war and I was coming in as an outsider. The idea to focus on young girls came only after I moved to Grozny and started befriending girls my age. I slowly started to understand what it meant to be a woman living in a conservative, male-dominated region. Most never finish school and use marriage as a gateway to finding independence and gaining respect from society. The Chechen president himself publicly stated that women are the property of their husband and their main role in society is to bear children.”

Amina Mutieva, 21, a student at the Islamic University in Grozny prays in a prayer room for women. © Diana Markosian/Reportage by Getty Images

Why are young people embracing Islam in Chechnya? Is religion willingly adopted or imposed by the power?

“Islam has been a part of the Chechen identity for more than 500 years. But, for decades, all religion was banned under the Soviet Union. Now the current government has gone out of its way to aggressively present Chechnya as Russia’s new up-and-coming Muslim region.

“In part, I think the youth are embracing Islam because they don’t have a choice. Many women have been harassed and some physically harmed by bands of men for not wearing headscarves. Despite the separation of Church and state under Russian law, Chechen schools must now promote Islam. There are prayer rooms in just about every school, mosques are packed with worshipers every day, and the hijab is becoming increasingly popular.”

How is the older generation responding to this revival of Islam?

“The older generation is against it. They grew up under the Soviet Union where religion was repressed. There was one mosque in the neighboring republic of Dagestan, but only men were allowed to worship there. At that time, married women in Chechnya covered their hair with a small, triangle-shaped scarf as a sign of respect and modesty. So this new trend of covering one’s neck and chest with a hijab, which is promoted by fundamentalist Muslims, is not welcomed as it is not considered to be Chechen.”

Layusa Ibragimova, 15, has her hair and nails done before her wedding. Her marriage to 19-year-old Ibragim Isaev was finalized by her father just weeks before. © Diana Markosian/Reportage by Getty Images

Why did you name the series Goodbye My Chechnya?

“There’s an archive of letters and poems at the library in downtown Grozny. I came across a poem written by a 15-year-old girl who described her anger with war after losing her brother and finding her home in ruins. She wrote that it was no longer her Chechnya and no longer a place she could identify with. This encapsulated the story I was trying to tell about a new generation who is redefining what it means to be Chechen in a region once ripped apart by two bloody wars.”

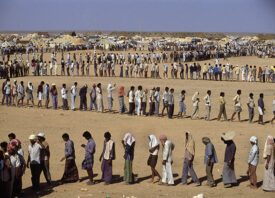

A group of Chechen women standing at the opposite end of the men. In Chechnya, under strongman Ramzan Kadyrov, gender segregation is being enforced.

Traveling to North Caucasus is notoriously dangerous, can you tell me about your trip(s) to Chechnya? Did you ever feel in danger?

“It is not so much dangerous now as it is unpredictable. The region has witnessed long periods of deportation, violence, suppression, and war. So there’s a heightened state of paranoia and fear among Chechens and also of the government.

“As a photographer, it is an extremely difficult place to operate. I was detained more than a dozen times by authorities. They’d question me, take my finger prints, mug shot and then let me go. It became somewhat of a routine. My phone was also tapped and I was followed on many of my shoots. It was an intense experience, especially since I was always alone. I don’t think I realized how much it all affected me until I left.”

I know you previously said you felt blessed to be there. Why?

“I think this experience broke something in me. I never expected myself to care as much I did while working on this story. The Caucasus became a part of my life. And these girls allowed me to be in their lives not just as photographer, but also as a friend.”