Search this site

In France, One Village Sets an Example by Helping Refugees

Michelle Baillot (center) picks up three sisters (from left: Touana, 5, Schkourtessa, 7, and Erlina, 10) from school. Baillot welcomed the family when the parents fled Kosovo after conflict engulfed the former Yugoslavia. (Lucian Perkins)

Marianne Mermet-Bouvier (far right) shelters a Syrian family who fled Aleppo. Her relatives hid Jews throughout the war and she says that there remains an unbroken line of tradition extending from that generation to her own. (Lucian Perkins)

In the yard of the stone elementary school with the tile roof in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, a town of just 2,700 people on a high plateau in south-central France, kids play and horse around like school kids everywhere. Except they sometimes chatter in different languages: They’re from Congo and Kosovo, Chechnya and Libya, Rwanda and South Sudan. “As soon as there’s a war anyplace, we find here some of the ones who got away,” says Perrine Barriol, an effusive, bespectacled Frenchwoman who volunteers with a refugee aid organization. “For us in Chambon, there’s a richness in that.”

More than 3,200 feet in elevation, the “Montagne,” as this part of the Haute-Loire region is called, first became a refuge in the 16th century, when residents who converted to Protestantism had to escape Catholic persecution. In 1902, a railroad connected the isolated area to industrial cities on the plain. Soon Protestants from Lyon journeyed there to drink in the word of the Lord and families afflicted by the coal mines of Saint-Étienne went to breathe the clean mountain air.

Thus Chambon-sur-Lignon, linked to Protestant aid networks in the United States and Switzerland, was ready for the victims of fascism. First came refugees from the Spanish Civil War, then the Jews, especially children, in World War II. When the Nazis took over in 1942, the practice of taking in refugees—legal before then—went underground. Residents also helped refugees escape to (neutral) Switzerland. In all, people in and around Chambon saved the lives of some 3,200 Jews.

The tradition of opening their homes to displaced people continues today. In the village of Le Mazet-Saint-Voy, Marianne Mermet-Bouvier looks after Ahmed, his wife, Ibtesam, and their two small boys, Mohamed-Noor, 5, and Abdurahman, 3. The family arrived here last winter and live for now in a small apartment owned by Mermet-Bouvier. They lost two other children during the bombing of Aleppo, and then spent three years in a Turkish camp. That’s where the French government’s Office Français de Protection des Réfugiés et Apatrides found the family. But even with entry papers, somebody in France had to put them up. Their sponsors, not surprisingly, were here on the plateau. Ahmed and his wife, now six months pregnant, smile often, and the word that keeps coming up in Ahmed’s choppy French is “normal.” Despite the upheavals of culture and climate, Ahmed finds nothing strange about being here, which, after the hostility he and his children encountered in the Turkish camps, was a thrilling surprise. “Everybody here says bonjour to you,” Ahmed marvels.

Margaret Paxson, an anthropologist who lives in Washington, D.C., learned recently that she has family ties to Chambon and is writing a book about the region. “This story is about now,” says Paxson. “Not because we need to turn the people who live here into angels, but because we need to learn from them.”

Read the rest of Joshua Levine‘s article and see more of Lucian Perkins‘s photographs over at Smithsonian Magazine.

Le Chambon-sur-Lignon resident Hervé Routier, 75, volunteers his time to teach French and other skills to refugees (Lucian Perkins)

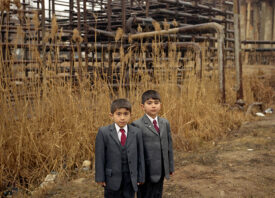

Left, inside the Chambon-sur-Lignon train station hangs a photo of rescued Jewish children and their documents. Right, Albanian refugees Anisa, 7, and Elivja Begilliari, 4. (Lucian Perkins)

Images © Lucian Perkins, Text © Joshua Levine for Smithsonian Magazine