Search this site

Diane Arbus and Her Brother Howard Nemerov: A Stunning New Book Shines Light on the Artist and Poet

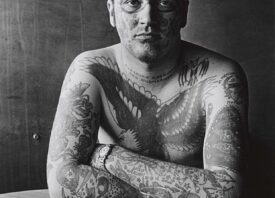

Diane Arbus, Untitled (7) 1970-71

Gelatin-silver print, 20 x 16 inches (sheet)

© The Estate of Diane Arbus

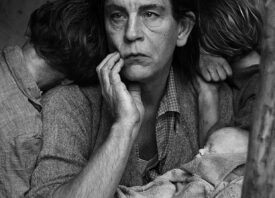

Part of the magic of the work of Diane Arbus’s work lies in the fact that no matter how exposed and vulnerable her subjects may be, they almost always remain enigmatical, as if they alone carry the answers to the great riddles of existence. Arbus’s nephew, art historian Alexander Nemerov, acknowledges this paradox in his book Silent Dialogues: Diane Arbus and Howard Nemerov, even as he tries to unpack the intricately woven threads of her life and work.

The book, composed of two essays, is an exploration of Arbus’s relationship with the author’s father, poet Harold Nemerov, tracing the unconscious and conspicuous parallels that run through their respective life’s works. Despite the poet’s distaste for both his sister’s content and her chosen medium, motifs large and small bind his words with her imagery, as if, as Arbus herself once put it, their “dreams people[d] each other’s.” Just as Nemerov begins the book with Arbus’s photograph Identical Twins, Roselle, New Jersey, 1967, the poet and the photographer become like twins possessed of both an uncanny psychic resemblance and irrefutable differences. Ultimately, through the currents of sibling rivalries and divergent feelings, Harold Nemerov’s poetry emerges as the narration we never knew Arbus’s photographs needed, illuminating the darkened, mysterious corners of her frame.

Perhaps the most ingenious aspect of the Silent Dialogues is that the author himself gradually emerges as their third participant. He is simultaneously the prolific Stanford professor and scholar Alexander Nemerov and the young child whom Harold Nemerov took to his first day of school, a day he recounts vividly in his text. As an art historian on this topic, he can never be objective, and that is what makes him the perfect person for the job. The artworks of Arbus and the poetry of the elder Nemerov are seen here through the veil of the younger Nemerov’s memories, or as the case is with Arbus, the absence of memories, allowing the book to exist in the exquisite space between scholarship and memoir. We talked with the art historian about the book.

Silent Dialogues is published by Fraenkel Gallery and is available here.

Do you think you approached this project any differently than you did your other books? In what ways did your personal relationship with your subjects color your study of them?

“I tried to write the book swiftly, on the current of my feeling. In that sense, it’s like the other books I’ve done recently. I don’t think my personal relationship to my father and aunt colored my study, except in the way you’d expect: that it gave me some sense, from the inside, of the right questions to ask.”

You mention that you have no memories of Arbus. Has making this text helped you to get to know her, or does she remain as much an enigma as ever?

“Writing the book brings me closer to her work and to her as an artist. A more serious and fearless example I could not hope to have. That said, I do not feel that I have brought her near to me. She is close because she is far away.”

Was there a specific moment when you began to trace the links in their work, or did it happen over time?

The basic premise–that my father and aunt are more artistically related than anyone might think, more related than my father would have ever thought–came to me pretty much at once. Like it was the thing to say. To this day, I don’t know why this was the thing I felt I had to say.”

You write on the “religion of art” and on art that touches on the spiritual realm beyond that which is visible to us. In what ways has this kind of art-making faded? Is there hope for it’s return?

“The idea of the artist as a truth-teller–as getting something just right, some little corner on the way things actually are–is, yes, very much lost. Or rather it is still present but largely hidden or repressed or denied. One proof that it still exists, however, is the stunned response to Arbus’s photographs to this day. The same goes when people hear a good poem such as many of my dad’s read aloud. It stops people in their tracks. That power of art and poetry is still there. Teaching is one way to bring it out. Mostly though it’s a lost art–people are often too glib, too assured, or too scrupulous and cautious, to avow the experience of being moved, stunned, stopped in their tracks, by a poem or a work of art.”

Silent Dialogues: Diane Arbus & Howard Nemerov, Published by Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco