Search this site

Playing War Games on American Soil, in Photos

“We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality,” Karl Rove told the New York Times Magazine in 2004, under the guise of anonymity as a “senior advisor” inside the Bush II White House. By playing a page from his own book, Rove’s words and actions served to underscore the wisdom of Edgar Allen Poe who sagely advise the American public, “Believe nothing you hear, and only one half that you see.”

It’s apt guidance for anyone engaged in political theater, be it as a participant or mere observer. We are surrounded by fictions masquerading as fact, narratives and ideologies designed to prop up systems of power for reasons we may never know that trade on our fears and desires, beliefs and hopes. At a time when “fake news” is both a truth and canard, we’re living in a hall of mirrors that doubles as an echo chamber.

Yet regardless of what reality we hold in our mind, there is simply the fact that another one is playing out every day in real time. In 2016, photographer Debi Cornwall began visiting ten military based across the United States to create her new book, Necessary Fictions (Radius), which has just been short listed for the 2020 Rencontres d’Arles Photo-Text Book Award. Selections of work from the series are now on view in “Leica Women Foto Project Exhibition” at Photoville in Brooklyn, NY, and Leica Women Foto Project Award Exhibition ar Leica Gallery in Boston MA.

Back in 1983, the American public was held spellbound when a young hacker unwittingly accessed a US military super computer that innocently asked, “Shall we play a game?” in John Badham’s Cold War sci-fi film, War Games. In retrospect, the early Matthew Broderick vehicle seems quaint. The threat of nuclear war was real, but a slacker hacker as the unwitting protagonist a touch absurd.

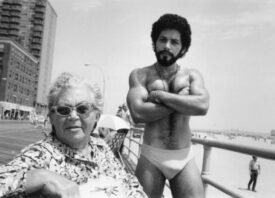

But perhaps fiction is less disturbing than fact, as Cornwall’s tour or the “fantasy industrial complex” reveals. In Necessary Fictions, Cornwall documents mock-village landscapes in the fictional country of “Atropia” and its denizens, costumed Afghan and Iraqi civilians, many of whom have fled war, now recreating realistic training scenarios in the service of the US military. “We are patriotic Americans,” one role player from Afghanistan tells Cornwall.

Real soldiers, dressed by Hollywood makeup artists in “moulage” (fake wounds), then pose front of camouflage backdrops, turning the entire exercise into a performance — but for whose benefit, and at what cost? These are just some of the questions Necessary Fictons raises, but answers do not easily come. Here Cornwall shares her journey into the dark heart of America.

To begin we would love if you could share what inspired you to take up photography as a second career in 2014 after you worked for 12 years as a civil rights lawyer handling cases of wrongful convictions and police shootings?

“I had freelanced for a newswire and worked for documentary photographers Mary Ellen Mark and Sylvia Plachy in college but the job I landed out of college was as an investigator and trial assistant for the federal public defender’s office. That led me toward law school and a career as a civil-rights attorney. By 2014, I was itching to be creative again, still looking at questions of power but from a new vantage point, fueled by curiosity rather than outrage.”

Could you share some of the lessons you learned working with Mary Ellen Mark and Sylvia Plachy, and how their approaches to photography may have informed or shaped the way you think about visual storytelling?

“I worked in Mary Ellen’s library when she was in the process of digitizing her archive, so I saw years of her contact sheets. It felt like this was a rare opportunity to understand the way she approached documentary photography. I learned from her not just to make the photograph you thought you wanted and move on, but to get to know the people you’re looking at. Spend time, build relationships. And keep making photographs until you get it right.

“I printed for Sylvia in her home darkroom when she was at the Village Voice. Fine-tuning each print for publication was its own incredibly valuable education in looking and seeing. What I remember most from that experience was Sylvia’s warmth, her generosity, the stories she told over lunch in the garden each Saturday afternoon that summer. That planted a seed about what an artist’s life could be.”

What was the inspiration to create Necessary Fictions, and what are the key themes you wanted to explore in this body of work?

“Those in the ‘reality-based community’. . . believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality. . . That’s not the way the world really works anymore. We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality.”

“This 2004 quote from George W. Bush’s chief political strategist, Karl Rove, opens my book, because Necessary Fictions is about ‘state-created realities.’ The project developed as a result of my experiences making photographs at the offshore prisons of the U.S. Naval Station in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, for my first book, Welcome to Camp America (Radius, 2017).

“The U.S. military controls everything there, including who gets to visit, what you see, and which images you may leave with. I was told that, ‘Gitmo is the best posting a soldier could have. There’s so much fun here!’ Which obscured a much darker truth about what was happening to the men held for years as uncharged ‘War on Terror’ detainees. Reality was stage-managed for public consumption. At the same time, I spent long days with military escorts, who told me their Iraq and Afghanistan war stories to pass the time. I began to wonder about the human experience of preparing for war, wrapping one’s head around the enormity of it.

“In my research, I discovered something that encapsulated both of these questions: military sites across the United States where mock villages populated with costumed Afghan and Iraqi civilians hosted realistic, immersive military wargames for soldiers and marines preparing to deploy. In my new book, these photographs are interspersed with text that asks larger questions, about the performance, commodification and consumption of war and its impact on us all.”

Could you speak about being inside the war set for “Atropia” and the ways in which the construction of this fictional country conflates aspects of the military, Hollywood, and media narratives to create a “training ground” for soldiers who may one day be sent to war in the Middle East or Afghanistan?

“There’s a critical theory term I learned in college that I never thought I’d use again: simulacrum. In sociologist Jean Baudrillard’s framework (Simulacra and Simulation, 1981), it’s a copy without an original. But it came to mind as soon as I set foot on the first mock village. The idea of these spaces and scenarios is to construct an environment that is close enough to what soldiers will encounter when deployed—the sights, sounds, and even smells of battles in foreign lands—that they already have sense memory when they arrive.

“To me these sites felt like stage sets gesturing in the direction of realism, of over there, and yet were unquestionably a product of here, of American contractors who build the sets, who cast and costume the roleplayers, of Hollywood makeup artists who are flown in between Hollywood film gigs to paint the soldiers in “moulage” (fake wounds), for mass casualty-event training. Author Ben Fountain coined the term, ‘fantasy-industrial complex,’ and I felt as though I had discovered its epicenter. The text in my book expands on this idea.”

Could you speak about the idea of objectivity in photography, and the way in which it has long been used to maintain ideologies of Western cultural hegemony under the guise of “fair and balanced” reporting?

“I agree with the premise of your question, of course. Tomes have and will continue be written on this subject. I’ve been asking this question of myself from the beginning. My senior college thesis involved examining three bodies of photographs of Native Americans: the staged portraiture of Edward Curtis, my own documentary photographs of Narragansett people in Rhode Island, and their family photographs.

“I came to understand that my vision was not ‘objective,’ but necessarily influenced by my own lived experience and subject position as a white American woman. My thesis essentially reasoned me out of pursuing social documentary photography. It took me 18 years doing other things to return to visual expression. Now I make work that tries to visualize invisible systems of power and their impact on society. If I’m looking to expose the performance of power, its staged show, I have to keep the same critical eye on myself.”

Could you speak about the role advocacy plays in your photography, particularly when you are working in highly sensitive environments within the military industrial complex?

“As a lawyer, I was seeking concrete results on behalf of a client, whether compensation or systemic reforms that would help others as well. As an artist, I’m looking at similar kinds of questions, speaking to both the personal and the systemic, but I’m under no illusion that my work will have tangible results. My goal now is to understand. And to facilitate a conversation.

“When making work I am professional and respectful toward individuals, even as I am critical of the operation of state power. Certainly I have opinions, but the point is not so much to express those views as it is to invite viewers to grapple with these questions along with me.”

At what point did you begin to think about the idea of a “fantasy industrial complex” and what does this suggest about the nature of empire in the United States?

“As I was starting my research on Necessary Fictions I discovered a remarkable novel, Ben Fountain’s Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk. It’s hilarious and profane and dark, all at once, in telling the story of a decorated 19-year-old Iraq War veteran who is caught up in the media circus of a publicity tour culminating in the halftime show at a Thanksgiving Day Dallas Cowboys football game. It completely captured the complicated mood I was developing in my own work.

“I was able to contact Ben in 2017, and he sent back a speech he had given to the Air Force Academy where he spoke about the “fantasy-industrial complex,” this web of iProducts and Instagram feeds and memes and games and stuff that distracts us from looking at how state power shapes our lives, who it serves, and what it is doing in our names. This concept really resonated as I made Necessary Fictions. So much so that a quote from his speech appears at the end of my book.

“If we are comfortable and consuming and distracted, then we aren’t concerned. We are less inclined to look, or to see clearly. It’s not a coincidence that the scaffolding of the fantasy-industrial complex is increasingly exposed now, in this year of COVID lockdowns, international borders closing to us, the rising tide of mass protests against police violence, and a presidential election inundated by ‘fake news.’ Within what may be the first moment of national discomfort in many of our lifetimes, the nature of American empire is laid bare.”

Lastly, why do you think so many Americans (and for such a long time, so much of the West) bought into the fantastical narratives about “fighting for freedom and democracy” when there has been so much evidence to the contrary?

“This kind of state messaging is reinforced in so many ways—in our textbooks, our news media, our movie culture, what is considered acceptable to say and what is off limits, what is considered ‘patriotic’—and it also taps into a deep human need to be the “good guy” in the stories we tell about ourselves. We inevitably cast ourselves as the protagonist, the star, in the movie of our lives. It’s probably the most fundamental question I’m asking in my work: what if we’re not ‘the good guy’?”

Ongoing Exhibitions:

Photoville, Leica Women Foto Project Exhibition. Sponsored by Leica Camera USA. Through November 20, 2020 (Outdoors, Brooklyn Bridge Park, under the Brookyn Bridge)

Leica Women Foto Project Award Exhibition, Leica Gallery, 74 Arlington St, Boston, MA 02116, through November 30, 2020.

All images: from Debi Cornwall: Necessary Fictions, published by Radius Books © 2020. All images © Debi Cornwall. from Debi Cornwall: Necessary Fictions, published by Radius Books © 2020. All images © Debi Cornwall.