Search this site

Looking at Race, Gender and Sexuality Outside of the Binary

Before the onslaught of gentrification, the San Francisco Bay Area was one of the most radical cities in the nation. With the advent of the jazz scene and the Beat poets of North Beach, the hippie counterculture of Haight-Asbury, the Gay Rights Movement in the Castro District, and the punk scene of the 1970s, San Francisco was one of the rare places where the fringe was always centered.

Although the city has changed radically with the tech boom, there still remain radical enclaves. Deep in the mix is photographer Jamil Hellu, who has developed a distinct visual vocabulary examining the intersections of cultural lineages and queerness over the past decade.

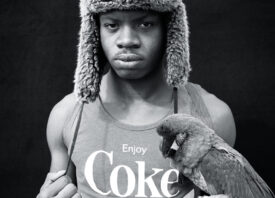

His new exhibition, Together, now on view at SF Camerawork through March 14, 2020, explores issues of identity relating to race, gender, and sexuality. The exhibition features photographs and video installations that highlight Hellu’s use of self-portraiture and representations of queer visibility engaging the Bay Area’s diverse LGBTQ communities to create a symphony of contrasting queer voices that co-exist simultaneously.

Hellu’s work defies the limits of binary thinking that have created reductive ideologies used to exploit and oppress those who are not members of the ruling class. By rejecting the oppositional perspective and hierarchical model of binary thought, Hellu restores the integrity and complexity of human existence to those who refuse to shrink themselves to fit into a model that excludes or demonizes their truths.

Hellu’s vibrant, colorful images are a statement of the power of visibility: a refusal to be marginalized or erased. They hold power by asserting themselves as icons in their own right and on their own terms. Hellu uses humor and contrast to shake off the assumptions we hold and the labels we apply to that which pushes beyond the confines of our comfort zones.

Here, Hellu explores how discrimination and intolerance shape personal histories, and uses the camera as a tool for social change, empathy, and agency. He gives voice to his subjects in the captions of the work, allowing us to acknowledge them on several levels at the same time.

“I am a queer black person. As a descendant of the Southern slave trade, I’m flipping the script of patriarchy,” says Beatrice Thomas. “Like the Black Panthers, I’m a protector of my community, claiming female power” — a powerful nod to the political party founded in Oakland, which brought the conversation of Black nationalism to a global audience.

“Out in the world, I often experience a quizzical gaze from people trying to decipher my gender.” says Leila Weefur, recognizing that most people are unable to deal with ambiguity, and desperately cling to the few labels they know, despite the fact that they are inaccurate.

It’s a telling realization about the struggle to leave binary thinking behind — so many do not want to understand what challenges ideas that aren’t even theirs. Many would prefer to allow someone else to do the thinking for them, so long as they can maintain the small sliver of power in an outdated, unjust hierarchy. But as Hellu’s work reveals, it’s much too late for that.

“Beauty comes from within,” says Sister Tilda NexTime, a member of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, an order of queer and trans nuns. “You only see the beauty in me because you have a divine beauty inside of you.”

All images: © Jamil Hellu