Search this site

Sam Gregg documents the true story of Naples

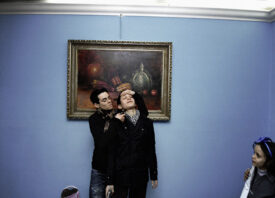

Whether its the slums in Klong Toey, Bangkok, or Britain filled with “greasy spoons” and “pie and mash shops”, London-based Sam Gregg is a portrait and documentary photographer drawn towards capturing marginalised and dispossessed communities.

Through honest and captivating imagery, Gregg encompasses his environment by fully immersing himself in his surroundings. Over the years he’s formed a body of work that’s full of impactful stories and narratives – so enlightening, so vulnerable and so empowering that it’s hard to witness any of his collections come to an end.

Within See Napes and Die, his ongoing project that began in 2016, Gregg travels to four of central Naples’ most historically rich yet volatile areas: Rione Sanità, Quartieri Spagnoli, Forcella and Santa Lucia. With an aim to “humanise the city’s plight” while “showing that those who are affected are tangible human beings before they’re political units” – says Gregg in the summary, the series is a response to the media and its glamorisation of Naples’ negative image.

The title “See Napes and die” derives from a phrase coined by German writer and statesman Johann Wolfgang Von Geoth – famed for four novels, poetry, prose, verse dramas, memoirs, literary and aesthetic criticism to name a few. It’s said that in 1786-88 he made a journey to Italy, which later inspired his play Iphigenie Auf Tauris and Römishe Elegein, a series of poems.

And most poignant was his use of the phrase espoused in his book Italian Journey in 1986 – written during the time of the golden age of Spanish Bourbon rule, where Naples was considered one of the most opulent cities in the world. “So much so that many found it impossible to leave, only doing so upon dying,” says Gregg. “In a modern context, the phrase is a tongue-in-cheek reference to the over-documented gang violence of the city.” Although Naples regularly tops the European crime index rankings, the area is still steadily improving.

Over the course of two millennia and the aftermath of the fires of Vesuvius – the violent eruptions that destroyed Pompeii – Naples’ derived a cacophony of noise and colour forged from its rich blend of cultures. Gregg adds: “At a time when nationality and immigration is centrefold to Italian current affairs, the story of Naples, both past and present, is one to be upheld as a symbol of cultural consolidation.” His documentation as such is an honest take on the spirit and vibrancy of the people who live in these areas, despite the difficulties they face in times of adversity.

“A port city with a labyrinth structure and fluctuating economy, Naples has, over the years, proved to be the perfect breeding ground for radical thought. From the Neapolitan Femminiello (one of the earliest definitions of gender nonconformity) to the birth of the Camorra (the oldest criminal organisation in the world), the city is akin to a densely packed pressure cooker with many forced to escape the tensions of reality through non-conformist measures,” says Gregg.

“This is no more evident than in the volatile central areas of Rione Sanità and The Spanish Quarter, where the bulk of See Naples and Die was shot. The residents from these zones firmly believe that they’re cut from a different cloth. They way they talk, the way they dress, and indeed the very physical make-up of their being is different.”

He concludes: “Even in the face of prejudice, they embrace their differences wholeheartedly, and ironically, although they strive for singularity, they are comprised of diversity.”

All images: © Sam Gregg