Search this site

The Artist Decolonizing the Idea of Africa

The search for knowledge, wisdom, and understanding lies in the process of distilling fact from fiction, truth from lie, meaning from myth. It is the sifting through appearances where deception flourishes, in search of the source of authenticity and integrity upon which existence takes root.

“One consequence of Eurocentrism is the racialization of knowledge: Europe is represented as the source of knowledge and Europeans, therefore, as thinkers,” photographer Gloria Oyarzabal observes, recognizing the systems of power profiting off this misinformed belief.

These systems of power feed off a form of colonization that extends beyond the centuries-long rape, pillage, and enslavement of the people and the land — it is the colonization of the mind, a far more insidious programming that is more difficult to detect and eradicate, for its forms are multifarious, moving like a virus from one person to the next.

The programming runs so deep that many will fight to defend its dastardly deeds before doing something so honorable as change their mind. Often times, the programming only ends when one finds it is too foolish and disgraceful to hold irrational thoughts. Then it becomes a process of decolonizing the mind of the bankrupt ideologies and logical fallacies one has been fed throughout their lives, and do the work of self-education, recognizing that blind spots will be revealed.

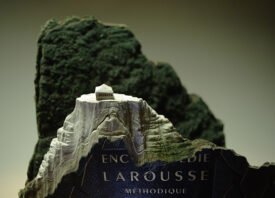

In her series, Woman go no’gree, Oyarzabal has done just this in a photographic exploration of gender, history, knowledge-making, stereotypes, and clichés of Africa. Using a mixture of archival colonial images mostly found in magazines, street photos taken with a digital camera, and studio photography found or made during her artist residence in Lagos in 2017, Oyarzabal employs a visual language that subverts and spellbinds in equal part, leading us into a silent realm of symbol and iconography. Here, Oyarzabal shares her journey with us.

Could you speak about the inspiration for Woman go no’gree?

“Well, if I look back, maybe it comes from my years living in Mali from 2009-2012. I was surrounded by a social structure that was an absolute matriarchy and at the same time women had real equality problems. My indignation clouded my capacity for analysis and balanced judgment. I tended to compare it with the processes of Western feminist struggle. ERROR!!! I say it now with a bit of shame: my reaction was one of a typical empowered and privileged white bourgeois woman.

“Years later, after a few projects in which I focused on the Machiavellian creation of ‘The Idea of Africa,’ I ended up in the processes of colonization of the mind. I discovered Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Chinua Achebe, writers who talk about how European civilization appropriates the African world and how Western influences like language, religion, and social structures changed African societies — not only geopolitically but psychologically, spiritually, and mentally.

“In the summer of 2017 I was selected to do an artist residency that offered me the opportunity work in in Matadero Madrid (Spain) and Art House Foundation Lagos (Nigeria), on a project called ‘Susanne and the Elder,’ inspired by Artemisia Gentileschi’s story. I linked this amazing painting with what happened at that time on the African continent with the Transatlantic Slave Trade and the situation for women in this horrifying nightmare.

“At the end of the residency in Madrid, before going to Lagos, I exhibited the project as a multimedia installation with sculpture, photography, projection, and a consultation table of African feminist literature. One of those books was Oyèrónke Oyewùmí’s The Invention Of Women: Making An African Sense Of Western Gender Discourses, where she traces the misapplication of Western, body-oriented concepts of gender through the history of gender discourses in Yoruba studies.

“Her analysis shows the paradoxical nature of two fundamental assumptions of Western feminist theory: that gender is socially constructed and that the subordination of women is universal. This book demonstrates, to the contrary, that gender was not constructed in old Yoruba society, and that social organization was determined by relative age. So, before English colonial years, empowerment in Yoruba society wasn’t linked to gender.”

Could you speak about the importance of decolonizing gender?

“To colonize means ‘To occupy a territory far from its borders in order to exploit it and dominate it administratively, militarily and economically.’ But we shouldn’t forget that there’s also the colonization of the mind. Through language, thought manipulation, and privacy invasion, the mind configures a state of vulnerability that makes the path of dependency propitious, and hardly impossible to defend their own dignity.

“For this reason, the colonization of the mind constitutes a subtle and alienating practice that, many times, those who execute it in the various intangible planes of daily life do so in the name of morality and of values and customs that are mentioned and proclaimed with the trick of deception.

“This promotes the propitious field for individuals to be colonized by the values of others, by the tastes and preferences of others, by imposed customs and prejudices, by religions and fanaticism, by family mandates, by culture and by possessions derived from a consumerism that limits the expansion of life. This is how mental submission leads to a lack of objectives, favors laziness and leaves the person at the expense of the decisions of others, weakening his ability to react to injustice, corruption and abuse.

“Empires, by their very nature, embody and institutionalize difference, both between metropolis/colony and between colonial subjects. Imperial imaginary, for good or bad, floods popular culture. Gender categories were one kind of ‘new tradition’ that European colonialism institutionalized in Yoruba as well as other African cultures. Before colonization social practices (division of labor, kinship, professions and monarchical structures) were not ordered according to gender difference but to lineage.

“Let’s try to think of gender as a Western construction. The three central concepts that have been the pillars of Eurocentric feminism (women, gender and sisterhood) are only understood with a careful attention to the nuclear family from which they have emerged. Feminist concepts arise from the logic of the patriarchal nuclear family, which is far from universal.

“Let us wish for new ways of relating genders, of new models of intercultural dialogues not based on supremacy nor on an excluding hierarchy, and maybe identities, both individual and community, could naturally develop towards a society which one wouldn’t have to be invisible in order to advance.”

Could you discuss the ways in which photography becomes a tool for expanding and redefining the terms of the conversation?

“I think that anyone who reflects, discusses, believes, philosophizes around a transcendental issue for society is positioned in the creation of discursive, vindictive and activist tools. The writer, the musician, the dancer, the scientist or the poet generate languages, which are more or less accessible, more or less opaque, but always with an intention. Each one with its channels, its ways of accessibility for a specific public.

“Perhaps the great advantage of photography is the democratization of a tool that facilitates a discourse. Now, more than ever, everyone is susceptible of being a narrator, bearer of fantastic stories…or a liar. Already in the Bauhaus era, Moholy-Nagy anticipated that ‘Whoever that could not read a photo would be the illiterate of the 20th century.’ This idea of ‘reading’ photography takes us to a new conception that is very narrative, even cinematographic.

“We’re already bored of talking about the millions of images generated per second in the different social networks, of followers, likes or haters, of post- photography… but the truth is that we are ‘homo visualis’ and what you can generate in the narrow way retina-brain is effective, fast and powerful. For good or for bad.

“We are in the era of the ‘Fury of Images,’ as Fontcuberta says. And it can degenerate and corrupt an imaginary, do a lot of damage. I appeal to the responsibility of the imaginary generator. Anyone of us could be one! Let us be really consistent with what we show and narrate, ethically correct with our responsibility as imaginary generators. Photography can move mountains! I am a great believer in how photography can transform a discourse, change a gaze, raise passions, rewrite history, change judgments, and cleanse glances.”

Could you speak about the significance of the title, Woman go no’gree, and the reference to the Fela Kuti song?

“The title is a phrase that you find in Fela’s song Lady, and it’s a quite controversial song as, depending on the reader, it has many different readings. Most discussions have pondered whether Lady was misogynist or feminist without reaching a consensus. Actually it’s ‘Woman no go’gree,’ which is in lingua franca pidgin and means something like ‘woman will not listen, or won’t be agreed.’ I changed the order of the words.

“Lady came out in 1972 on the Shakara LP, twelve years after Nigeria had gained independence from the British and two years after the end of the Nigerian civil war. It was also the year that revenue from oil sales boosted Nigeria’s economy to such an extent that people’s salaries were in many cases doubled. It seems fair to assume from the lyrics that during this time of change, a parallel discussion about African women becoming Westernized was taking place.

“Fela Kuti was a cultural critic and he was way ahead of his time in pointing out the consequences of bad political leadership in Africa. But when it came to women, Fela’s politics was a bit weird. In this song, on one hand, seems he condemned African women who were independent, defiant, outspoken, and westernized. In Fela’s mind, the true African woman pretty much does what her man tells her to do. In this sense the song is a condemnation of women’s liberation from patriarchal, servile roles.

“On the other hand, despite its display of male-dominant attitudes, it is also a song that demonstrates African women’s power to self-define. There is even a sense of affection and pride towards the lady’s display of power when Fela says ‘I wan tell you bout lady [..] Hmm, I neva tell you finish.’ It may or may not have been Fela’s intention to demonstrate the no-nonsense attitude many Nigerian women flaunt upon a man who tries to subjugate her, but in the very line, ‘She go say I be lady o,’ this matter-of-fact self-determination is represented. Furthermore, by rejecting the idea of the emancipated, liberated lady, Fela was inadvertently opposing Western cultural dominance.

“But most of the women in Fela’s life were, however, powerful. His mother, Funmilayo Kuti was a card-carrying Communist. Her story was one of the many driving forces that inspired the wave of feminism that swept through Nigeria in the 80’s. So, in a way, the song contradicts Fela’s own life and the women in it.

“Another problem is that both the African woman and the lady in the song are mere symbols of essentialist cultural wars between Western and African men. And there is also the aspect of the depiction of the traditional African woman that in Lady is biased. In fact, some of the most important African feminist icons, including Fela’s mother, were traditional African women too.

“Last year the song was remixed by Angelique Kidjo, Akua Naru and Questlove ‘reclaiming “Lady” for modern African women,’ because a new reading of the meaning of the song is taking place as a commentary on gender and the intersections of ethnicity, modernity, class and tradition. Lady tackles some of the key issues in African feminist thought and is a valuable contribution to gender politics in post-colonial Africa.”

All images: © Gloria Oyarzabal