Search this site

Eugene Richards Looks Back at a Life in Photography

Eugene Richards, Snow globe of the city as it once was, New York, New York, 2001.

Gelatin silver print. Collection of Eugene Richards.

Eugene Richards, Grandmother, Brooklyn, New York, 1993.

Gelatin silver print. Collection of Eugene Richards.

More than half a century ago: the New Journalism came of age — a style of reportage so wholly unlike what came before that made it clear the seeming “objectivity” espoused by the Western eye was blind to its own innate biases. Rather than continue to presuppose one could be disinterested in covering subjects like Civil Rights and the Vietnam War, many journalists took a stand, opting to explore the complex truths of human life during the final half of the twentieth century — including their own.

Like W. Eugene Smith before him, photographer Eugene Richards (b. 1944) used the photo essay as a means to engage with his subjects through the profound transformation that comes when human beings not only connect, but are seen, heard, understood, and able to share their lives in a holistic way.

Throughout the course of his career, Richards has focused on the essential experiences of life that are daily fodder for headlines including birth, death, poverty, prejudice, war, and terrorism. But through Richards’s lens, we come to understand just how little we know — and how deeply reliant we are upon those who do the reporting in our stead.

In Eugene Richards: The Run-On of Time, now on view at the International Center of Photography through January 6, 2019, we are given a stunning trip through Richards’s life in photography. The exhibition and accompanying catalogue distributed by Yale University Press serve to remind us that we are responsible for evaluating not only the content but also the quality and caliber of the source itself. It is not enough to be talented and to have mastered technique; one must stand for something, and in doing so, use their skills in the service of the greater good.

Here, Richards shares his extraordinary journey, that includes a healthy dose of skepticism about the photograph itself.

Eugene Richards, Wonder Bread, Dorchester, Massachusetts, 1975.

Gelatin silver print. Collection of Eugene Richards.

Could you take us back to growing up in Dorchester during the 1950s and ‘60s, and how your upbringing informed your position as a conscious objector of the Vietnam War?

“I grew up a little Catholic boy in Dorcester, MA. I was kind of shy, pudgy, in a neighborhood that I didn’t realize how secluded we were racially. And now I think back on it, it was pretty sad and closeted, but when you’re a kid, you don’t know. So maybe that’s the first hint of it, that something was amiss .I think that was the biggest thing in retrospect.

“I wasn’t religious, but I took a lot of stuff to heart. Naive things sounded like the Ten Commandments, and I heard that stuff. And that echoed in the media of our time, which is interesting. The media when I was growing up were comedy shows, westerns and that kind of thing. There was a good guy and a bad guy, and the bad guy was bad, and the good guy was basically…moral. You learn moral lessons for a man.

“Those are the list of forces: TV and religion. And shyness. And I think that maybe those things come together to make you wonder about things like war, like what are we doing and why are we doing it, and do you take war very personally. I always looked at war in two ways: what does it do to a country? But, also, what if it was us? And that’s where I think a lot of it came apart. What would I do if something came into my country? I started saying I would do the same thing a lot of other people would do. You would be forced to defend your family. So that’s what I was thinking.”

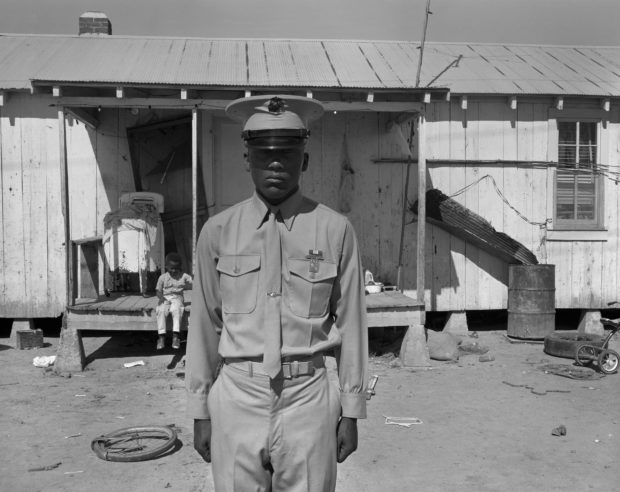

Eugene Richards, U.S. Marine, Hughes, Arkansas, 1970.

Gelatin silver print. Collection of Eugene Richards.

Can you share how the creation of Respect, Inc. provided you with firsthand knowledge and understanding of the challenges facing low-income communities in the South?

“My understanding of that came from joining VISTA (Volunteers in Service to America), and I was at VISTA for like eight months, and in that eight months, I saw the lives of sharecroppers, and the racial separation. You didn’t so much even see it, as sense it, and know it — that there were multiple cultures that were in everything. When I got kicked out of VISTA, (because I was too politically active), Respect Inc. was a continuation of that. It gave us a little newspaper to report with….”

At what point did you recognize photography as a tool of activism, and your weapon of choice?

“I saw photography as a tool of activism when I was in the South. Basically, we used the camera right away to illustrate the poverty, and the things we had seen. We also used it to raise money for the organization and the newspaper and also for health clinics. That’s why I started photography.

“As for a weapon of choice –I’m not sure it is the weapon of choice today. I distrust visuals, so you can’t simply expect the photograph to be totally honest. If we’re talking about Vietnam, we were using the same bombing pictures to be both pro- and anti-war. With the Iraq War, we all watched with shock and awe. Some people thought it was a celebration; other people thought it was the beginning of the end of the world. So, I don’t know about visuals being an outright proper weapon.”

Eugene Richards, Peter’s Rock Church, Marianna, Arkansas, 2010.

Chromogenic print. Collection of Eugene Richards.

Could you speak about the subjects that have most affected you throughout your work?

“The more obvious ones—like photographing my first wife Dorothea’s Breast Cancer treatments. I look at it now — I don’t think I did all that I should have. But, I did the best I could, because I didn’t want to take photos at all of that. She wanted to have those pictures made. That experience, of course, stayed with me.

“People stay with you that you would never expect. For the series shot for Time magazine on end of life, I ended up meeting an oncologist in New Jersey who had cancer. He was just a great, intellectual sweet guy. I went out there to take pictures of him, and he asked me to stay with him, which freaked me out a little bit. But, I realized he wanted a person outside of his family who kept doting on him just to stay with him. And I did for a day or two. And then he went and died on me. I was there because it was the end of life, but I never got over it.

“He knew everything that was going to happen, of course. The thing that impressed me about him is that reminded me of my first wife (Dorothea) in the sense that he didn’t want to-he wanted to be alive at any means. He did not want to be put down – so to speak. He said that he knew it was going to hurt, and Dorothea was the same way. She said, ‘I want to have every second.’

“We never get rid of the people who I photograph. They’re always there. People call us all the time. They write us. They pop up. There was a family reunion for a woman that I had met in about her life, and that became the centerpiece of the family reunion. So that was pretty cool. 1980. A really impoverished sharecropper, and I told the family that I had a tape of her talking.”

Eugene Richards, “Crack Annie,” Brooklyn, New York, 1988.

Gelatin silver print. Collection of Eugene Richards.

Could you speak about the challenges of producing work like Cocaine Blue, Cocaine True in the United States at a time when the government was rapidly expanding the prison industrial complex?

“I don’t think they’re related. I think they are in the sense that the things were happening at the same time. But trying to do a book like Cocaine at any time is not the easiest thing to do because there was no financial support for it. The publisher is not going to get the money back they know it’s going to be controversial. It takes a massive amount of generosity to get it out.

“And I don’t think people, even at that time, understood how massive and separatist the prison system was. It’s always been, like anything, like with the drug problem, it’s probably there right in front of you. People didn’t realize how profitable it was; how vast it was; how discriminatory it was. Now knowing that more than we knew it back then.”

Could you speak about your decision to work in color and how this informs your process?

“I didn’t make a decision to do it; I got on assignment to do it. I ended up photographing, and it was the right decision, old houses on prairies and in North Dakota and places like that. And I found out that if you did the black and white, it looked like a Depression area, but if you did it in color, it was very beautiful. The wallpaper, and the picture the color made things more today.

“And I think that’s difference for me today. Black and white very rapidly, and it always did to me, feel like a memory and color is more contemporary. Even in your way of thinking it is.”

Eugene Richards, Still House Hollow, Tennessee, 1986.

Gelatin silver print. Collection of Eugene Richards.

Lastly, in light of the state of America in 2018, what are some of the fundamental lessons gleaned throughout your career that could inspire or empower readers to become the change they want to see in the world?

“We have to face the fact that it’s a very difficult time, and things are changing. I think at one time, it was enough to have talent, and curiosity was admired… just plain old, blatant curiosity. If you saw people that you didn’t know that you wanted to know, you would go there, meet them. It worked out, or it didn’t work out. People liked you; people didn’t like you. But basically, curiosity was manifest to what we do.

“Now, it’s down to whether you have the right to be curious about certain people, to look at people. And it’s more of an issue of whether you’re the right gender or sexual persuasion or color. That’s a totally understandable movement that could be graceful…but also could end up something that achieves just the opposite — like a lack of rapport and a lack of looking at ourselves, and I mean that literally.

“Now, if there’s an assignment, I wouldn’t get it. Whether I should or not is debatable. But I think part of the time what makes me a good observer is my ignorance. Take my work photographing women in labor. When I go to take photo of a birth, I clearly don’t know anything about it…I personally don’t know how it feels. But, I want to see if I can show how it feels in a picture.

“Unfortunately, nowadays, it’s beginning to be at the point where you have to be preordained…. you have to know in advance what you’re looking for. We’re becoming illustrators instead of journalists.”

Eugene Richards, PTSD, McHenry, Illinois, 2014.

Chromogenic print. Collection of Eugene Richards.

All images: © Eugene Richards