Search this site

Words & Pictures Collide in Teju Cole’s New Book

Teju Cole, Brienzersee, June 2014.

Archival pigment print, printed 2017.

Description:

I opened my eyes. What lay before me looked like the sound of the alphorn at the beginning of the final movement of Brahms’s First Symphony. This was the sound, this was the sound I saw.

Teju Cole, Zurich, November 2014.

Archival pigment print, printed 2017.

Description:

A length, a loop, a line. Faraway wave seen from the deck of the ship. I think the Annunciation must have happened on a day like this one. Stillness. In the interior, she reads with lowered eyes, unaware of what comes next. A presence made of absence, the crossbar, the cloth, the wound in his side.

The relationship between image and text is one of the most challenging pairings to exist. They demand complete attention and so one must choose: to look or to read—and in what order?

Perhaps it seems deceptively simple: one simply does as they are inclined. Yet regardless of preference, they inform each other, infinitely. When we read, we see the picture in our mind. When we look, we write the words ourselves. Now we are asked to forgo our imagination and focus on the given context.

Yet few can bridge the gap that exists between the linguistic and visual realms, the distinctive forms of intelligence that operate independently and interdependently at the same time. Most often, we simply opt out somewhere along the line, wanting to return to the freedom to imagine for ourselves rather than listen to what we are told.

Writer Teju Cole understands this well. As photography critic for the New York Times Magazine, Cole has mastered the painting pictures with words that illuminate and elucidate in equal part so that his words both add and peel back layers from that which appears before our eyes. As an author of Open City (2011) and Every Day is for the Thief (2014), Cole crafts entire worlds inside the written world, evoking the very experience of life itself.

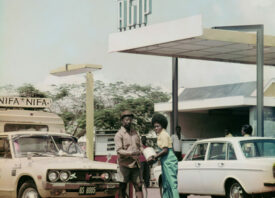

Now, in his first solo show, Teju Cole: Blind Spot and Black Paper at Steven Kasher Gallery, New York, on view through August 11, 2017, the writer brings us along for a journey around the world, looking at life in Capri, Zurich, Lagos, Saint Moritz, Chicago, Nairobi, Brooklyn, Seoul, and more, where we see life not only through his eyes but experience it through his prose.

The exhibition, which accompanies the publication of his fourth book, Blind Spot (Random House), features a selection of 30 color photographs accompanied by a single paragraph. Each piece of text is a beautifully encapsulated prose poem that draws us into uncharted depths, giving voice to the image that quietly beckons us with its simple, subtle lyricism of color, shape, and form.

“A length, a loop, a line. Faraway wave seen from the deck of the ship. I think the Annunciation must have happened on a day like this one. Stillness. In the interior, she reads with lowered eyes, unaware of what comes next. A presence made of absence, the crossbar, the cloth, the wound in his side,” Cole writes in dense, intense, luminous prose that accompanies a very tight frame of a curtain hanging from its frame, with just a sliver of the velvety blue sky of Zurich peaking through.

Here it is that life occurs, the setting where existence unfolds as thought, action, word. Cole’s words act as a voiceover, setting the scene… Or is it his photographs that illustrate the space in which these events occur? It need not be either/or but a new paradigm: both, at the same time, in an endless cycle of back and forth, just as occurs every moment we are present and aware of the fact that we are both act on the environment as the environment acts upon us. In this way Cole’s photographs come alive, creating a new level of possibility that exists within the interconnection between that which we think and that which we see.

It is the gift of sight that Cole celebrates, for one morning in 2011 he awoke blind in one eye. The cause was papillophlebitis, perforations to the retina that made it impossible for him to perceive depth so that not only was he unable to see, but he had trouble walking.

As one who had always taken to the street, able to move among the people, sharing their world and their experiences through his prose, Cole’s illness struck him on several levels at the same time. “The photography changed after that,” Siri Hustvedt writes in the book. “The looking changed.”

Blind Spot is the result. In these works, Cole moves through the landscape and the cityscape without making a sound, seeing life as it unfolds as a something we pass through, rarely taking note of the setting of our lives—the veritable context in which existence takes place. So often we skate across the surface of things, seeing, but never looking, at the nuance and complexity.

In this way, Cole’s words make us pause and reflect, not simply on what lies before our eyes but the ways in which context acts upon our perception of self. The photograph acts as a memory, freezing time forever more, so that we can move in between our inner and outer lives, considering that ways in which the mirror each other infinitely, able to see beneath the surface of a thousand dreams.

Teju Cole. Zurich, July 2015.

Archival pigment print, printed 2017.

Description:

I sat there for hours and watched the sun slip across the landscape. Anything can happen. The point is to shatter serenity; the absurdity of contrast between before and after is the very point. It could be in a shopping mall, a cafe?, a public square. It could be in a restaurant or at a concert, in the places where people gather and are happy. I am haunted especially by the innocuous phrase I saw in a news article —“in hotels popular with Westerners”—for these are the most frequent targets, and these are the places where I spend my days and do my work. (I write these words in yet another hotel in yet another city.) But in the places I don’t live, in other cities, in remote borderlands, on farms, what happens also happens there, and it happens just as suddenly, just as grievously; but less visibly. I remember this: against the impassioned claims of the nascent Black Power movement in 1966, Martin Luther King, Jr., driven to exasperation, said to a Mississippi gathering: “I’m sick and tired of violence. I’m tired of the war in Vietnam. I’m tired of war and conflict in the world. I’m tired of shooting. I’m tired of hatred. I’m tired of selfishness. I’m tired of evil. I’m not going to use violence no matter who says it!” I sat there for hours, in one of those hotels popular with Westerners, and watched what Roethke called “the deepening shade.”

Teju Cole. Muottas Muragl, July 2015.

Archival pigment print, printed 2017.

Description:

In the spring, I twice watched Olivier Assayas’s Clouds of Sils Maria, in which a woman (Maria Enders, as played by Juliette Binoche) said: “I had a dream. We were already rehearsing, and past and present were blending together.” And I really did not know in that moment if I was dreaming, or remembering a dream, or watching a film, or remembering the first time I watched the film and heard Juliette Binoche say those words. In the summer, I went to the Engadin and Sils Maria for the first time, half in pursuit of this dream. In the fall, looking at the photograph I had made on the mountain and writing about that visit, I could not say for sure whether on that cloudless evening on Muottas Muragl, overlooking the Engadin all the way to Sils Maria, I had remembered the dream by Maria Enders, or whether I had only later dreamed that I had remembered it there.

Teju Cole. Sasabe, September 2011.

Archival pigment print, printed 2017 .

Description

Far from the city. Through narrow darkness, through scrub forests and rocky cliffs, our Elder Brother brought us across, his name was I’itoi. On our setting out from the other side, he turned us into ants. He brought us through narrow darkness and out at Baboquivari Peak into this land. Here we became human again, and our Elder Brother rested in a cave on Baboquivari, and there he rests till this day, helping us. The land is a maze. You have to be guided through, right from the beginning you had to be guided. The first story in the world is about safe passage. An iron fence spirals into the distance, enforcing on the land a separation in the mind. In the grass near the inspection post at Sasabe, on the Mexican side, someone has planted two white crosses. The large one lists at a sixty-degree angle. On the smaller one, you can see the word “mujeres.” The code is made of wounds.

Teju Cole. Basel, November 2014.

Archival pigment print, printed 2017.

Description:

Color is the sound an object makes in response to light. Objects don’t speak unless spoken to. An

object does not have a color, it makes a color (the way a bell makes a sound). Sound is molecular motion. Color, too, is molecular motion. Color is the selective absorption and emission of light on the surface of an object. As an untouched drum makes no sound, an object in total darkness has no color. A photograph full of muted but complicated color is similar to a full orchestra playing a quiet passage: powerful resources used to create a subtle effect. With my eyes I begin to hear what I see.

Teju Cole. Zurich, 2014.

Archival pigment print, printed 2017.

Description:

Kitchen to living room. Bedroom to bathroom. Downstairs to get the mail. House to subway. An evening stroll. You take around 7500 steps each day. If you live to eighty, inshallah, that comes to 200 million steps over the course of your life, a hundred thousand miles. You don’t consider yourself a great walker, but you will have circumnavigated the globe on foot four times over. Downstairs to get the mail. Basement for laundry. Living room to bedroom. Up in the middle of the night for a glass of water. Walking through the darkened house, you suddenly pause.

Teju Cole, Beirut, May 2016.

Archival pigment print, printed 2017.

Description:

The Poets light but Lamps—Themselves— go out—The Wicks they stimulate—If vital Light Inhere as do the Suns—Each Age a Lens Disseminating their Circumference—— Emily Dickinson Poets die. They must. But the poems, if vital, give a light that each future age refracts in its particular lens. No, not “give a light”: they “light inhere”: contain in themselves a light from which they cannot be separated. Like the sun, they illuminate and yet remain perpetually illuminant. Another poem of Dickinson’s, “The Tint I cannot take—is best”—which I didn’t know or don’t remember —cut me to the quick in part because, a couple of weeks ago, I developed a roll and found it empty: thirty-six lost shots. I had failed to engage the sprockets in one of my manual cameras. And so each time I framed a shot and clicked the shutter and advanced the film, I was fooling myself. Well there it was, an anxiety dream come true. But Dickinson’s poem, luxuriating in optics, also contains the line “The fine—impalpable Array—That swaggers on the eye.” I take this as a reminder that what is seen is greater than what the camera can capture of it, what is known is finer than writing can touch. My eye was swaggered upon. I wasn’t fooled.

Teju Cole, Brooklyn, April 2015.

Archival pigment print, printed 2017.

Description:

The stage is set. Things seem to be prepared in advance for cameos, and even the sun is rigged like the expert lighting of a technician. The boundary between things and props is now dissolved, and the images of things have become things themselves. Perhaps the artificer’s gold paint is still wet on such scenes in which we play at kings. Wandering around, I find this theatricality of city life especially visible at the edges: the sleeping docks, the decrepit industries, the disused railroads: at such places, the city is shorn of all superfluity and reduced to its essentials, as in a play by Beckett. Flutes! Drums! Let the players in.

Teju Cole, Capri, June 2015.

Archival pigment print, printed 2017.

Description:

Later on, I thought of the catalogue of ships in the Iliad. “I could note tell over the multitude of them nor name them, / not if I had ten tongues and ten mouths, not if I had / a voice never to be broken and a heart of bronze within me, / not unless the Muses of Olympia, daughters / of Zeus of the aegis, remembered all those who came beneath Ilion.” But that was literary, that came later. On the day itself, on the evening of the morning in which I opened up the window of my room to see the apparition of a shining fleet on the Mediterranean, what I thought of was what Edna O’Brian said to those of us in the audience: “We know about these beautiful waters that have death in them.”

All images © Teju Cole, courtesy of Steven Kasher Gallery.