Search this site

‘Raising a Family Behind Bars:’ Portraits of Family Life Taken in a Remote Prison in the Philippines

My fixer had arranged for a hasty portrait session to take place that day. Much to my surprise, all of the families had continued to live alongside the inmates and wardens. I decided to take the portraits in various corners of the prison. The portraits that I am presenting represent a small sampling of the many families that I photographed.

A warden gathers the “trusted inmates” in the courtyard of Leyte Provincial Jail for an informational meeting about my visit and to check attendance. Allegedly, I was the first Filipino American to ever set foot within the compound. Thanks to my fixer, Damian Acosta of the political party, Akbayan, I was able to gain entrance.

Out of a remote prison in the Philippines, New York-based photographer Lawrence Sumulong brings us images of wrenching despair, penury and bleakness. But in his collection, “Raising a Family Behind Bars”, there are also examples of unbearable lassitude and the kind of prolonged pointlessness that can only be found among people living in a place against their will. Sumulong documents families that, in the most extreme displays of desperation, have been forced by ruin to relocate from their home communities, still crumbling and broken months after Typhoon Yolanda, to live inside the walls of an island jail. There they joined relatives previously incarcerated, some enchained for petty crimes such as robbery and drug selling, others for murder and rape.

Sumulong, a proud Filipino-American, wished to see the devastation left in Yolanda’s wake with his own eyes. He felt that collecting portraits of those most directly affected would be a good way to do it. “The confluence of civilians, inmates, wardens, loved ones, couples, and families entrapped in an enclosure under desperate circumstances because of forces outside of their control felt universal and close to me,” says the photographer.

The families and prisoners mingle freely within the prison walls. At times, it felt more like a neighborhood. “With a water purifying system, electricity, rations, a sick ward, and security, the jail arguably provided more amenities than what one could find outside of the walls of the jail in the post-Yolanda landscape”, said Sumulong. One of the prisoner’s relatives had even set up a vegetable stand in the middle of the prison. Though even so, the place felt very much like a prison and prisoners were still exposed to disciplinary measures. One day they were made to construct a welcome sign. It lies on the towering hillside overlooking the jail yard, an arrangement of stones that read, “WELCOME LEYTE PROVINCIAL JAIL”.

The entrance to Leyte Provincial Jail. A sign in the hills had been built by the inmates and there was evidence that reconstruction efforts have been slow in the 6 months following Typhoon Haiyan. My assignment was to verify whether families of the inmates were continuing to live inside the destroyed jail, which was a story that the journalist, Aya Lowe, had originally broke. Leading up to my trip, there was news that access to the jail was restricted and the families had long since relocated.

The interior of one inmate’s “cell”. I didn’t have the insight into what the jail had originally looked like, but these newly reconstructed spaces seemed familiar and reminiscent of some of the homes that informal settlers or squatters would often build in various parts of the Philippines.

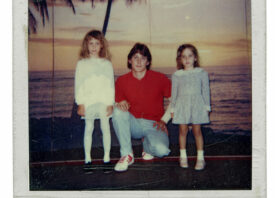

A couple stands for a portrait in the courtyard of the jail. In the background, a watch tower and a small outpost for the wardens can be seen. The atmosphere was surprisingly relaxed between the inmates, the wardens, and the families.

A family stands for a portrait in the courtyard of the jail. With a water purifying system, electricity, rations, a sick ward, and security, the jail arguably provided more amenities than what one could find outside of the walls of the jail in the post-Haiyan landscape.

A father and his daughter pose for a portrait outside their “cell”, which was a raised wooden floor with a blue tarp covering the majority of it for privacy.

An inmate stands for a portrait near the open air “comfort room” or restroom and shower area, which faced the wilderness and several large hills.

A family stands for a portrait in front of another inmate’s “cell”. The presence of family members made it difficult to ascertain and comprehend the crimes that the inmates had been accused of. I was told that petty crimes such as robbery and drug trafficking were the main culprits. However, upon looking at the makeshift release forms that I had asked each family and inmate to sign, murder and rape were the most prevalent.

A vegetable stand at night in the middle of the prison, which was run by a woman related to one of the inmates. It was unclear to me how she obtained these items and who she sold these goods to given the fact that the jail was an enclosed and remote community. Nevertheless, it gave the appearance of a local store that one might find in a small neighborhood or barangay.

This particular family, the Maanyo’s, had a baby at the jail (right) one month ago. Roberto and Jesusa had met and began their relationship at this prison.

An inmate’s family “cell” in which all of the members stay in one room. Like much of the destroyed jail, walls and dividers that often demarcate public from private space are non-existent.

An inmate’s family “cell” , which also serves as a “sari-sari” store. One inmate, Paul Gumaroy (not pictured), stated that this inmate and his family’s situation serve as a textbook example of the problems facing the current prisoners. With the loss of court records due to the Typhoon Haiyan, Paul feared that the judicial process has been completely crippled and the future of all of the inmates and the livelihoods of their families lies lost in limbo. Even before the disaster, this particular inmate had been residing at Leyte Provincial Jail for over 10 years awaiting a trial.

All images © Lawrence Sumulong