Search this site

Berenice Abbott: Paris Portraits 1925-1930

André Salmon (French, 1881-1969) &

Pierre Charbonnier (French, 1897-1978)

Mme. Guerin with Bulldog (French)

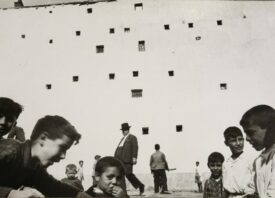

Paris, 1925: Berenice Abbott stood on the balcony of Man Ray’s Paris studio with his camera in her hands, taking photographs that would become the very first portraits in a long and legendary career.

Four years earlier, she arrived in Paris at the age of 23. Within two years, she was working as a darkroom assistant to her friend Man Ray. With his encouragement she stepped into the light and began producing work of her own. A selection of 115 works from this period now appear in the luxurious tome, Berenice Abbott: Paris Portraits 1925-1930 (Steidl), giving us an unfettered glimpse into the early years of a natural.

“The first [portraits] I took came out well, which surprised me,” Abbott is quoted as saying in the book’s introduction. “I had no idea of becoming a photographer, but the pictures kept coming out and most of them were good. Some were very good and I decided perhaps I could charge something for my work. Soon I started to build up a little business and I paid Man Ray out of the money I made for the supplies I used, but eventually I was paying him more than he was paying me and that’s when it started to become a problem.”

Indeed, the problem could only be rectified by setting up her own studio, which she did with the help of friends Peggy Guggenheim and Robert McAlmon. Here she used a 5 x 7 view camera to produce a series of plate glass negative, the majority of which are 9 x 12 cm.

Paris Portraits 1925-1930 presents a selection of the best work of this period scanned from the original glass negatives and printed in full. Every subject is identified and presented along with quotes from Abbott or background on the subject, providing a deeply intimate view into these quiet yet powerful photographs.

We learn that Lucia Joyce, daughter of novelist James and his wife Nora, aspired to be a dancer, only to see her dreams dashed at the age of 28 when she was institutionalized for schizophrenia and remained in asylums until her death at the age of 75. The sheer tragedy of what is to come just a few years away adds a layer of pathos and poignancy to Abbott’s alluring image of a young woman in search of herself.

Counter this image with the portrait of writer Pierre de Massot, who had been a secretary to André Gide. Og de Massot, Abbott observes “[He] was a dear person, trying to look tough here, but he wasn’t. A delicate French writer, he wrote one book entitled Portrait of a Bulldog, in which my photograph appeared. I tried to locate him when I went back to Paris in 1966 but no one had even heard of him.”

It is here at Abbott’s portraits cause pause, for it is in the fact that she chronicled this period in history that becomes more resonant nearly a century after the fact. Her work straddles the space between the classical and the modern, anticipating the importance of the portraits during the golden age of picture magazines. At the same time, her work embraces the traditions of the past, of the formality of recording the moment for posterity and creating a legacy designed to stand the test of time, and in doing so, bring us back to the genius of her work.

“I never look at two people in the same way and often look at the same person in different ways,” Abbott is quoted as saying. “This is why it was so hard, why I didn’t take twenty people in one day and make more money. I treated every session as though I had never taken a photograph before in my life, relying on the moment, on my reaction to the sitters, working together with them and thinking what to do with them and how to see them. I all came spontaneously with each person.”

This level of attention and care is evident in each work, revealing that what appears simple and intuitive still requires a level of mastery that can only be held by those willing to put in the work. Abbott understood that the practice was one vested in a principle deeper than that object itself, one that required a fresh perspective with each and every sitting. She revealed. “As I see it, the serious photographer is interested in the subject. Exactly the same way a scientist or a writer is…Or a dramatist or a musician, anything. It’s the subject. It isn’t just picture taking and picture making.”

Not even when the picture is all that remains of the person…

Lucia Joyce (Irish/Italian, 1907-1982)

Lucia Joyce (Irish/Italian, 1907-1982)

Pierre de Massot (French, 1900-1969)

Peggy Guggenheim (American 1889-1979)

All images © Berenice Abbott, from Paris Portraits: 1925-1930, published by Steidl