Search this site

Martha Cooper: Five Decades of Street Art and Culture Around the Globe

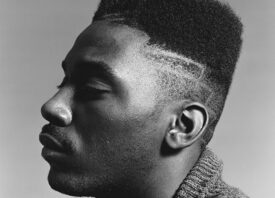

Christopher Sawyer breaking, Upper West Side, NYC, 1983

Christopher Sawyer breaking, Upper West Side, NYC, 1983

Couple with big boom box, Manhattan, NYC, 1983

Woman with white pants on 180th Street platform, Bronx, NYC, 1980

Woman with white pants on 180th Street platform, Bronx, NYC, 1980

Photographer Martha Cooper has always lived life on her own term. After graduating high school at 16 and Grinnell College at 19, the Baltimore-native decided to see the world so she joined the Peace Corps and traveled to Thailand, where she taught English for a spell. Then she hopped on a motorcycle and hightailed it from Bangkok to London, taking all along the way.

She received a diploma in anthropology from Oxford, which speaks to her truest sensibilities: her passion for documenting the creative fruits of the human experience. In her hands, the camera is not merely a tool to create an image for aesthetic pleasure, it does something more; it bears witness to a time and place that is inherently ephemeral: street art and culture, which is inherently urban folk art.

In 1970, Cooper found herself walking along a street in Tokyo when she spotted a man in a crowd. On his back was a Japanese tattoo, with figures drawn in the style of a woodblock print. Entranced, Cooper followed him until he disappeared, then began asking her friend about tattoos—a touchy subject. Tattooing had been outlawed in 1872, then legalized again in 1948, then quickly became a status symbol for the yakuza and the Japanese underworld. But Cooper is not one to give up when she has her sights set, and so she pursued her quest to completion: entrance to the studio of Horibun I, a tattoo master.

It is here, in his studio that Cooper made the photographs that comprise the earliest work in the exhibition Martha Cooper, currently on view at Steven Kasher Gallery, New York, through June 3, 2017.

The exhibition begins with a preview through Cooper’s early days in New York, shooting black and white photographs for The New York Post. Her assignment? Weather photographs. It all sounds very charming and innocent in light of the 24-hour news cycle that currently consumes us.

Enamored with the anything-goes atmosphere of New York in the 1970s, Cooper zipped through the city in a beat-up Honda Civic. Her friends said she drove like a cabbie, which she took as a compliment. The result was a series of photographs captured in New York State of Mind (Miss Rosen Edition/powerHouse Books), a couple of which have been included in the exhibition to give a taste of life on the street.

The Post’s offices were then then located on Manhattan’s famed Lower East Side.At the time, the LES was a rough and tumble place, suffering from the same “benign neglect” that plagued African-American and Latino communities across the United States. Yet, despite the systemic abuses of the government, the people of the LES were a live, vital bunch.

Cooper found herself intrigued by the games that kids played, whether riding on the backs of buses or rolling around inside tires. She began to create a body of work documenting their lives that went on to be published in the book Street Play (From Here to Fame). While photographing kids in the LES, she met a boy named Edwin who told her he wrote graffiti. He asked if she ever photographed graffiti and asked if she would like to meet the “graffiti king.” One thing lead to another and Cooper found herself in Brooklyn’s East New York, in the home of legendary writer DONDI.

Through this encounter, Cooper gained access to a secret world, invited on missions to the trainyards in the dead of night, when writers went to bomb. She was quickly hooked and quit her job at The Post to photograph graffiti full time, creating the iconic photographs that helped to launch graffiti worldwide with the 1984 publication of Subway Art (Thames & Hudson) with co-author Henry Chalfant.

The book, which is considered the “Bible” of graffiti, captured the second generation as they took the underground phenomenon above ground. Once the book was published, it traveled the globe, inspiring new generations of teenage kids to leave their mark on society in a way that no one could control. Cooper’s photographs of masterpieces rolling along the tracks and the writers who made these artworks became icons all their own.

But the city of New York was livid, and it tried to shut things down. All that resulted as graffiti writers moved from the trains back to the city streets. It was during this era that Cooper trained her lens of the tradition of memorial walls, which had flourished during the crack epidemic that claimed so many lives. She published R.I.P. Memorial Wall (Thames & Hudson) in 1994, a quiet little volume that revealed Cooper’s fundamental interest in the folk art of urban culture.

Ten years later, Cooper’s work returned to the fore. The 2004 publication of Hip Hop Files (From Here to Fame) delved deep into her archive, unearthing a broad swatch of graffiti and b-boy photographs. Publisher Akim Walta interviewed the people in the photographs, creating an oral history of the era—and once again Cooper was back on the scene.

By this time a new culture was bring born: street art. Forgoing the letterforms of graffiti, it embraced the pictorial traditions of murals and the techniques of aerosol art, and a new generation of artists was readily embraced by the art world. Cooper suddenly found herself in demand, as the photographs she had created were now being reproduced by artists like Shepard Fairey and Chris Stain to create street art works inspired by photographs from Street Play.

Cooper was getting invitations by the dozen to fly around the world, from Wynwood, Miami to Tahiti to document street art. She has traveled from the favelas of Rio to the townships of Soweto, crafting an incredible collection of work that is as vital and poignant as the golden age of graffiti. Because, in the end, what it’s all about is the power of the people and the magic of the street to produce populist art. The art Cooper documents does not belong in galleries or museums—but her photographs do. She is the bridge between two worlds that rarely rub shoulders.

Girls dancing to disco music from a bar against graffiti wall, Lower East Side, NYC, 1978

Two cops patrolling subway, Bronx, NYC, 1981

Japanese girl with tattoo, Tokyo, 1970

Japanese girl with tattoo, Tokyo, 1970

Banksy “Ghetto for Life”, 2014, Bronx, NYC, 2014

Shepard Fairey pasting colab image from Cooper photo (USA), Bronx, NYC, 2010

Painted train passing through Kliptown, Soweto, South Africa, 2013

Seth (France), Ono’u Festival, Tahiti, 2015

Memorial wall to Tony by Nicer, Bio, and Brim, Mott Haven, Bronx, NYC, 1992

Chris Stain & Billy Mode (USA), Brooklyn, NYC, 2015

Girl doing swan dive off rock, Coney Island, Brooklyn, 1978

All images © Martha Cooper