Search this site

69 Magnum Photographers Reveal Their Contact Sheets in New Book

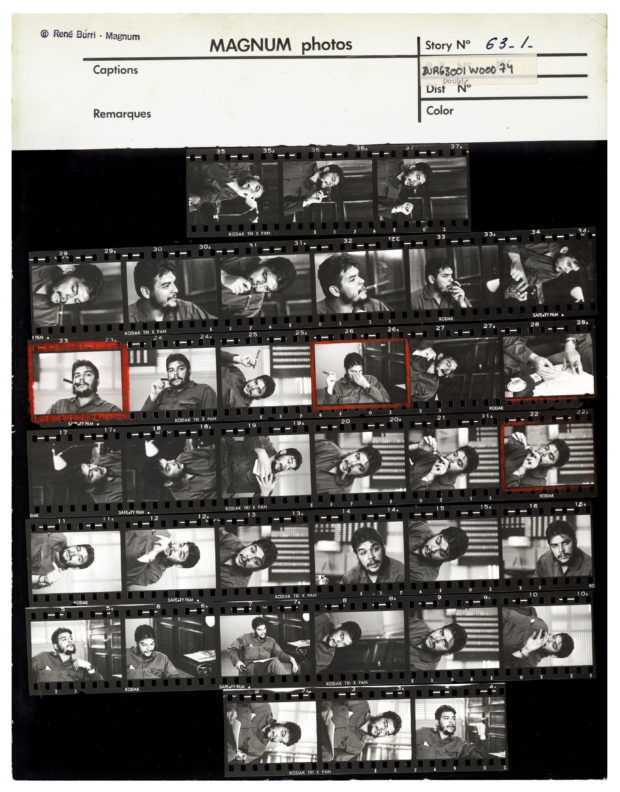

Havana. Ministry of Industry.

Ernesto Guevara (Che), Argentinian politician,

Minister of industry (1961-1965) during an exclusive interview in his office.

© Rene Burri/Magnum Photos.

We would like to believe that photographs convey an element of truth, that in the fraction of a second recorded for posterity, we have captured something that lies beyond mere celluloid of digital technology – something we can gaze upon and discover verifiable facts, unearth an ineffable aspect of reality that lies beneath the surface.

Perhaps this is possible, in as much as we wish to believe it so, but when we consider that the single frame lies in a larger body of work can we be absolutely sure that we’re not being guided by the aesthetic power of the form. Are we not sentient beings whose powers and perceptions of sight heavily influenced by the perfection of the art?

It may be the best way to know is to consider the context, in as much as it is available to us: the circumstances of the moment, the players, the photographer themselves. And, if we are to consider the artist, where does this image fall, not only within their oeuvre but more specifically in project from which it is drawn? This is where the contact sheet comes in.

Magnum Contact Sheets (Thames & Hudson) offers a critical look at the necessity of context in our understanding of the photograph. Featuring 139 contact sheets from 69 photographers, as well as zoom-in details, selected photographs, press cards, notebooks, magazine spreads, and texts by the photographer or an expert chosen by their estate, the book deepens our understanding about the photographic and editorial processes.

Filled with iconic moments that have become icons and artifacts, Magnum Contact Sheets revisits some of the most important historic moments in photography, including Robert Capa’s D-Day photographs made on the beach at Normandy in June 1944, Eve Arnold’s meeting with Malcolm X in Chicago in 1961, Susan Meiselas’ photographs of the Sandinistas in Nicaragua in June 1979, and Thomas Hoepker’s photographs made in Brooklyn on 9/11.

It is here, within this larger frame that we begin to realize “the decisive moment” is as much a skill for taking the picture as it is selecting it. The ability to discern the moment as it is happening requires the photographer to be fully attuned, to be perfectly present and connected to the energy of the scene as it unfolds.

Yet that is just one step of a much larger process, one that occurs by and large behind the scenes. Those who consume photos, whether in the media or in books, in galleries or in museums, or on the endless rabbit holes the Internet provides, rarely know the context from which the finished product arises. Here, in the contact sheets, we can see how it occurred, as well as discern other moments that might have been just as significant but were left behind.

Consider René Burri’s photograph of Ernesto “Che” Guevarra, taken in Havana, Cuba, in January 1963, which shows the revolutionary leader embodying the ethos of machismo, with a cigar clasped in his jaw while he looks past Burri, focused on someone outside of the frame. It shows Guevarra as the perfect mix of rebel and star, a handsome, virile young man who would be killed just a few years later.

“I remember when he bit the tip off his cigar,” Burri writes. “I expected him to offer me one, but he was so immersed in the discussion, which was lucky for me because I was simply ignored for two whole hours. He never once looked at me, which was extraordinary. I was moving all around him, and there isn’t a single photograph in which he appears to be looking at the camera.”

Guevarra’s focus marks him as an extremely confident man, one who required no reassurance about how he looked or how he would be portrayed – and that’s what comes through in all of the photos. His power and strength are both graceful and mesmerizing. The choice of photo is notable for both the lack of information about where he is and the placement of the cigar. It is a jaunty, energetic portrait that welcomes you into his spell. It tells us what we want to believe and it encourages our faith.

Magnum Contact Sheets reminds us a photograph is as much as a fact (who, what, where, when) as it is a manifesto (why, how). It is as much a poem as it is a polemic to be savored in both style and substance. You can skate along the surface or dive into its depths, for the single frame is just the tip of the iceberg.

Iran. Tehran. 1986. Veiled women practice shooting on the outskirts of the city.

© Jean Gaumy/Magnum Photos

All Images: From Magnum Contact Sheets: Compact Edition, Edited by Kirsten Lubben, Thames & Hudson.