Search this site

The Overlooked Value of Motherhood Revealed in Photos

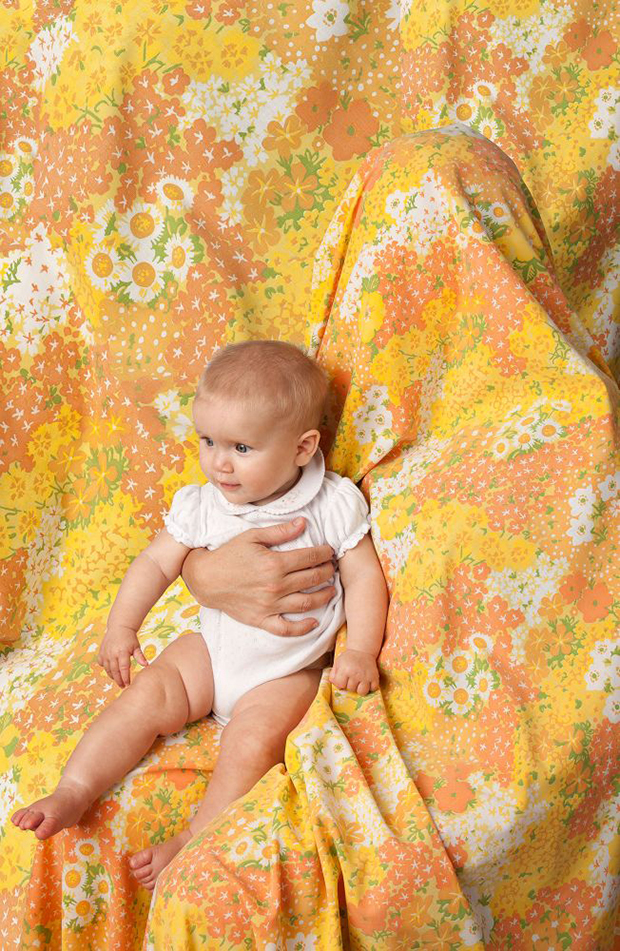

Hidden Mother: Eileen

Hidden Mother: Jenn

“I come from a long line of matriarchs and feminists,” New Mexico photographer Megan Jacobs tells me. “Both my grandmother and my mother were fearless in their times.” Now a parent herself, the artist drew inspiration from old images from the Victorian era to create Hidden Mothers.

It started with the 2013 publication of The Hidden Mother by Linda Fregni Nagler, a book of more than 1000 collected daguerreotypes, tintypes, ambrotypes, and other early photographs of babies, all of which include a mother who has been in some way erased from the picture. Usually, by a veil or shroud of some kind.

The reason for this technique was simple: people wanted photos of their babies for their albums and cabinet cards, but exposure times were long, and little ones have trouble holding still for seconds and minutes at a time. The solution was for the mother to hold the infant in place while cleverly disguising herself in the background. Sometimes, it’s hard to distinguish the women from inanimate objects like a chair or a set of heavy curtains.

Poignantly, it’s sometimes only way historians have been able to realize if a child was living or deceased. If a baby passed away, which happened frequently in the 1850s, they would be immortalized in a photograph after their death. If the mother can be seen hidden behind the child, it can usually be assumed that the baby was alive and moving.

For Jacobs, the Hidden Mothers became more than a historic quirk. They were symbols of the ways in which parents, and women in particular, are made invisible. She sees it in too-short maternity leaves. She sees it in the stigma that surrounds breastfeeding in public. And she sees it in the perceived gap between a woman’s identity as a mother and a professional.

“Mothers, many of whom work ‘second shifts,’ are left bifurcated: guilty for leaving their children while at work and longing to get back to work while in their children’s presence,” she explains.

For her own Hidden Mothers, Jacobs collaborated with friends and acquaintances from her parenting network, many of whom are in BabyMama Santa Fe group. The artist collected floral-patterned bed linens from family, friends, and thrift stores— a nod to the history of “feminine” or “domestic” motifs in art.

The shoots themselves were laid-back; often, the photographer’s kids were present, and some of the parents played peek-a-boo a bit to get their kids comfortable with the arrangement. The best part, Jacobs says, was talking with the other mothers. They all understood her intentions and her goals, and they were open with their feelings about parenthood.

Hidden Mothers was also an emotional project in some ways. There was one mother who had lost one of her children. “Before photographing her, I didn’t know her or that one of her children had passed on,” Jacobs admits. “She and I talked about how the loss of a child creates a space of uncertainty. She was a remarkable woman, and I was inspired by how she used the creation of her art as a means to begin to cope with the loss of her daughter.”

The photographer wove pieces of her own history and life into the images too. A few of the linens had once belonged to her grandmother, and her own children were often present on-set.

This practice of hiding mothers, often as they quite literally support their children, is an uncomfortable one, but in some ways, women have always been present to subvert that erasure. In the Victorian era, one of the few professions open to women was photography, and it’s been suggested that a significant number of the early photographs were made by female artists.

In covering the Hidden Mothers, Jacobs also leaves them exposed and vulnerable, and in making them invisible, she demands that they be seen. Some of the mothers who participated in the project have their portraits hanging proudly in their homes.

Hidden Mothers: D

Hidden Mother: Lisa

Hidden Mother: Lisa E.

Hidden Mother: Jessica

Hidden Mother: Sara