Search this site

The Photographer Who Used the Camera as a Passport to Freedom

After knocking repeatedly on Pablo Picasso’s door hoping to meet the master, a young college student by the name of Fred Baldwin was turned away. Then inspiration struck. Baldwin decided to pen a letter replete with illustrations hoping that the Spanish artist would chuckle in recognition and grant him access to his private villa in Cannes.

“Dear Monsieur Picasso,” Baldwin penned in script on July 28, 1955. “I am a student at Columbia University and this summer I am a freelance journalist. I know that you’re very busy but I am here in my car and each day that you won’t see me, my beard grows longer and loner. I will soon look like Moses. If you would let me take some color photographs then I could go to Florence where I have some money and cut off my beard.”

The extra effort finally did the trick, and the 74-year-old legend opened his doors to the ambitious young Baldwin. Perhaps he had recognized himself in another upstart who was both tenacious and unafraid to look the fool in order to pursue his dream.

Certainly, Picasso knew he had been had when he laid eyes on Baldwin, and asked him where his beard was. Quick on his feet, Baldwin quipped that what was on his face was all he could muster in three days, and with that Picasso laughed and told him to take all the pictures he desired.

That moment became a turning point in Baldwin’s life, an encounter of such power and significance that he chose to use it for the title of his magnificent new book — Dear Mr. Picasso: An Illustrated Love Affair with Freedom (Schilt) — a 704 page magnum opus filled with photographs and stories of a life spent behind the camera, traveling about the globe, pursuing the stories that spoke to his heart and soul.

For Baldwin, the camera was a passport to freedom, allowing him entrée to the place and situations that offered unlikely encounters with every corner of humanity. In 1958, he traveled to the Lapland region of northern Europe where he photographed a reindeer round up — which was rejected by National Geographic. Though the magazine had informed his worldview ever since he was an eight year old boy, Baldwin was not beholden to validation and recognition from outside sources in order to do his work.

He continued forth, photographing polar bears in the Arctic and fishing in Mexico, collecting stories and pictures from his journey to the far reaches of the globe. He loved to have tales he could share at cocktail parties to impress the likes of Ernest Hemingway, bon mots he could drop like bon bons and leave everyone’s jaws gaping with awe.

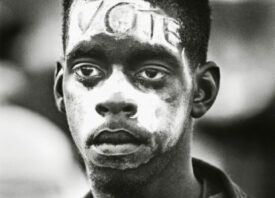

But then in 1963, he accidentally crossed paths with a Civil Rights demonstration in Savannah, Georgia, and he began to make photographs, feeling comfortable in the scene. “Again, my camera took me to where I would have never gone without it,” Baldwin writes.

“Ironically, I didn’t have to travel to the Arctic to discover unfamiliar lifestyles or people who were fundamentally different from me; I discovered them in my own backyard and in my head. Although African Americans represented a culture that I had been exposed to all me life, I began to see its people from a different perspective….And I was making photographs in a new way — for a cause, a cause I knew was right…. But now I was surrendering my secret God-given white self-importance; that was new.”

This sense of surrender would mark another turning point in Baldwin’s life and work, as he went on to join the Peace Corps the following year and began traveling through Malaysia, Afghanistan, and India before returning to Savannah in 1966. Having seen the world from so many vantage points, Baldwin settled down to focus on life in his backyard. Now 90, Baldwin remains a powerful force, driven by the understanding that the stories we tell have the power to shape and transform our collective lives.

All images: © Fred Baldwin