Search this site

Trauma and Hope in the Children of South Africa and Rwanda

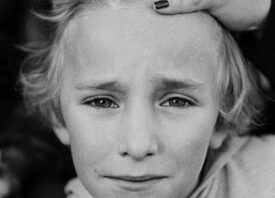

Pieter Hugo, Portrait #3, Rwanda, 2014 © Pieter Hugo, Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Pieter Hugo, Portrait #16, South Africa, 2016 © Pieter Hugo, Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

In 1994, photographer Pieter Hugo was eighteen years old. His home country, South Africa, had abolished apartheid three years earlier, and on April 27th, it would have its first election under universal adult suffrage. As millions lined up to cast their votes, some 3,000 miles away in Rwanda, an estimated 800,000 people were murdered. Millions fled, and as many as half a million women were raped.

Children born in South Africa and Rwanda after 1994 inherited both the victories and the traumas of their parents. In South Africa, this generation is sometimes called “the Born Frees.” In Rwanda, they are the “children of bad memories.”

Hugo’s original intention wasn’t to photograph the children, but when he was in Rwanda on assignment in 2014, a group of school kids took an interest in his camera, and he agreed to take their portraits.

The portraits in 1994, now on view at Yossi Milo Gallery, feature children from both countries. They are pictured in nature, sequestered from and unconfined by the world of grown-ups. Many of the children helped stage the images themselves. The lush surroundings have been taken by critics as a reference to the garden of Eden; Hugo himself sees echoes of William Golding’s lonely island from Lord of the Flies. In truth, the children in the pictures are likely residents of both mythological landscapes.

In their 2016 coverage of the work, The Times in South Africa suggests, “The images are not about the subjects, but about us.” The great poignancy of the pictures lies in the fact that the children, having been born after 1994, can’t possibly understand the full meaning of the images in which they play the central role.

Each of Hugo’s children gets a number, a location, and a date. Their identities are shaped not by who they are but by where they were born and when. The artist never tells us their names. The kids in Rwanda wear clothing several sizes too big, donated from Europe. The histories of these young people’s homelands will follow them, but they probably don’t know that yet.

Hugo himself is a father of two. His own children could have been included in these images. It might also be significant that in 1994, Hugo was on the precipice of adulthood himself. At eighteen, you don’t belong in the world of childhood anymore, but you’re still not grown. The artist is not a “Born Free,” and he’s not “child of bad memories,” but he has things in common with both.

The word “hope” has been much used in describing 1994, and it’s fitting— these children don’t have the same fears their parents did. They are safer. They are freer. Still, the hope is sometimes what stings the most. In this case, this hope of the younger generation is double-edged because it reminds us of a time when there was none.

See 1994 at Yossi Milo Gallery until March 11th, 2017. The book of the same name, published by Prestel, is available for pre-order.

Pieter Hugo, Portrait #1, Rwanda, 2014 © Pieter Hugo, Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Pieter Hugo, Portrait #7, Rwanda, 2014 © Pieter Hugo, Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Pieter Hugo, Portrait #19, South Africa, 2016 © Pieter Hugo, Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Pieter Hugo, Portrait #10, Rwanda, 2015 © Pieter Hugo, Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Pieter Hugo, Portrait #12, Rwanda, 2015 © Pieter Hugo, Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York