Search this site

The Mysterious Life and Work of Morton Bartlett and His ‘Family’ of Dolls

Morton Bartlett, Untitled (Girl Wagging Finger at Dog), c. 1955

Morton Bartlett, Water Ring, c. 1934

In 1963, the last of fifteen plaster dolls, twelve girls and three boys, were shrouded in newspaper and set to rest in individual wooden boxes, never to be opened again until 1993, the year following the death of their creator, the then-unknown photographer Morton Bartlett.

Over the course of the nearly three decades between 1936 and 1962, Bartlett devoted his spare time to crafting these would-be children, based in part from medical texts and charts. His hobby was largely a confidential one, but he nonetheless tenderly and meticulously sculpted these figures over the course of about a year each, outfitting them with detailed and delicate wardrobes as well as body parts that could be removed and refastened. Aged eight to sixteen, the effigies were complete with tiny fingernails and a wardrobe full of elaborate costumes.

A new exhibition at Julie Saul Gallery, where the dolls were in 2007 first seen in large-scale color photographic prints, reasserts the notion that Bartlett was first and foremost a photographer. The dolls were discovered untouched in the artist’s Boston townhouse by art dealer Marion Harris, who uncovered a wealth of photographs in which the plaster children were set up and engaged in various activities, from sightseeing to reading in bed. They were often accompanied by scaled stage props and backdrops to set the mood for their various childhood misadventures.

As illustrated by art critic and curator Michael Duncan, who writes the accompanying essay to the exhibition Family Planning: early photographs and archival material, Bartlett’s sculptures were closely predated by a time in which he photographed children for stock photographs (he was for a time a working as commercial photographer), which he later kept in carefully indexed and annotated cards, along with signed parental releases. Gestures now famous on the dolls are found reflected in his photographs of real, living children.

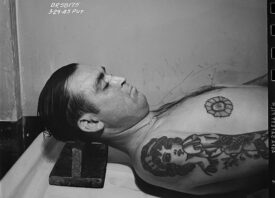

As much of Bartlett’s personal life remains an enigma, the motivations for his artwork—unrecognized throughout his lifetime save for a single story in Yankee magazine—are unknown. The few boys he sculpted, however, do indeed bear a likeness to the artist as a boy of eight, when he was orphaned and adopted into a new family. Though the extent of his solitude is debated, Bartlett never married or had children of his own. For Harris, the dolls become his family by proxy; others, like fellow photographer Laurie Simmons, liken him to a Humbert Humbert figure.

When Bartlett died, he left his estate to charities for orphans; he declined even to allude to the dolls in his will. Whether they served as his make-believe children or simply a hobby that he ultimately gave up, the remaining Bartlett sculptures, and the photographs that he made, exist in a world that because it so closely approaches reality can be nothing but a fiction, carefully constructed by one man for reasons unknown. From his work with children, and perhaps because of his own experience as a youngster, Bartlett carved out a simulated realm in which innocence need never fade into experience, and where children never grow up.

Family Planning: early photographs and archival material includes two of Bartlett’s doll heads alongside his photographs both of real children and the plaster ones. Also on view will be two self-portraits by the artist and his catalogue of release forms for the stock images. The show opens October 29th and runs through December 23rd, 2015.

Morton Bartlett, Ballerina, c. 1940 – 1950

Morton Bartlett, Untitled (Morton Bartlett with Camera and Girl), c. 1934

Morton Bartlett, See!, 1934

Morton Bartlett, Reading, c. 1934

All images © Morton Bartlett, Courtesy Julie Saul Gallery, New York